With the growth of social media and all the two-way channels of communication open to organizations, brand identity is potentially stronger but more at-risk than ever. Losing control of your brand’s ‘voice’ can be hugely damaging, and companies who have been brand-jacked, that is, had their brand hijacked, often move quickly to shut down the problem. But brand-jacking doesn’t have to be a negative thing, and companies who have learned lessons from the feedback it has given them can grow from the experience. Let’s look at the good, the bad and the ugly of brand-jacking.

Cultural awareness

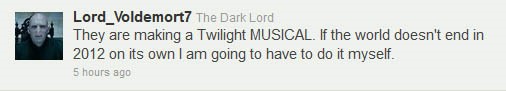

Writers who long for their characters to take on a life of their own would give their right arm to see their creations appearing on Twitter with their own profiles. Lord Voldemort, Darth Vader, Frodo Baggins and Edward Cullen all tweet regularly. Some accounts are more flattering to the original creation than others, and at some point brand managers have to decide how far they are comfortable in letting these unauthorized versions take the joke; AMC famously blocked the unofficial (but character-faithful) Twitter accounts of the Mad Men characters, only to backtrack when fans complained. AMC may have realized too late that social media character-jacking can be a sincere form of flattery and the ultimate proof that your fictional creation has made the transition to cultural relevance.

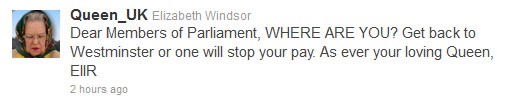

Identity jacking

Twitter-jacking isn’t limited to fictional characters. When your name is also your brand, this can potentially be very damaging. Celebrities and politicians have had their social media accounts hacked, and there can be multiple fake accounts for high-profile individuals at any one time. While Barack Obama, Sarah Palin, Britney Spears and Miley Cyrus have all been victims of malicious hacking, some fake accounts are more amusing than malevolent. Many are so obviously fake as to not cause offence or were created for a satirical or surreal purpose.

Bad PR

The creation of malicious fake Twitter accounts can be equally detrimental to companies and organizations. There have been many examples of Twitter accounts being hijacked in protest to a company’s unpopular policy or handling of an event.

Oil companies Exxon Mobil and BP have both been victims of Twitter impersonation, and following BP’s handling of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill disaster, the satirical @BPGlobalPR has attracted over 160,000 followers.

While this can be seen as a brand disaster, a company wishing to engage in some positive PR could use the feedback such channels offer to gauge the public’s perception and respond accordingly. Contrast the endless examples of companies who delete negative blog and Facebook posts with the policy of the@virginmedia team, who make a point of responding to every customer online mention whether it is positive or not. In one case, a woman tweeted that her Virgin Media connection wasn’t working and her two year-old daughter was upset at having to miss her favorite TV show, Peppa Pig. Not only did Virgin send an engineer round immediately, he was carrying a Peppa Pig toy for the little girl. Think what this type of response can do for your brand preference!

Fake Amazon reviews and tags

Following the popularity of the Amazon ‘The Mountain Three Wolf Moon Short Sleeve Tee’ prank, protesters have begun to use Amazon’s open review and tagging model to highlight unpopular products or issues. The pepper spray used in the UC Davis Occupy incident has been given over 360 tongue-in-cheek reviews on its Amazon page, as well as satirical product images and tags such as ‘tools of fascism’, ‘oppression’ and ‘police state’ (the product is currently listed as unavailable). Similar cynical additions have crept into otherwise serious product pages, particularly books by controversial public figures or products by companies with disputed ethical practices.

Aspirational branding

One problem facing aspirational, luxury brands is when their product is adopted by an undesirable demographic, which can lead to the alienation of their core customers. This occurs most commonly with name-checking by rappers or in popular culture although it is rarely a serious concern.

A more serious predicament is when the product has such an identifiable design that a mainstream take-over can have a disastrous effect. This happened in the 1990s in Britain to Burberry when its iconic tartan pattern became popularized by soccer players, then adopted by working-class fans who wore cheap imitations to such an extent that its customer base abandoned it in droves; the pattern had now become more identifiable with hooliganism than with style.

(Image: goodhumormarketing.com)

Knowing where to draw the line

Brand managers are always going to want to deal with a negative image but sometimes an over-reaction can lead to more bad publicity than simply doing nothing. The recent attempts by Stella Artois to move away from their ‘wife beater’ stereotype (the beer’s high percentage of alcohol had linked it with violence and anti-social behavior in Europe) backfired when changes to their Wikipedia page that removed the ‘wife beater’ reference were traced back to their own lobbying group. Given Wikipedia’s ethos of user-generated material, this led to a backlash that was quickly picked up in the press. The references were restored on Wikipedia but the negative publicity had already reached a far wider audience than would have ever read the original Wikipedia article.

The good side of brand-jacking

But image hijacking can work the other way. Corona was originally marketed in the USA as a Mexican beer for Mexican people, then was adopted by surfers in the 1970s who identified with it as a ‘beach beer’. They helped to popularize Corona among the wider population, and by the late 1990s it had overtaken Heineken as the number one imported beer.

Customer evangelism

It can be difficult for companies to let go of their tightly-controlled image and allow fans to steer the direction of a brand. But the enthusiasm of fans can be instrumental in popularizing products or media. Coca-Cola’s fan-created Facebook page was the second most popular page on Facebook in 2009; Coke asked to partner with them rather than demanding to take it down, realizing the power of fan-driven social media. Many brands choose to create an official page alongside unofficial ones knowing that heavy handed attempts to block fan pages can lead to a damaging backlash, although there is always the problem that a site’s popularity can be potentially damaging if it publishes unfavorable news or views about the company to thousands of followers.

Conclusion

The rise of social media has given customers unprecedented access to brands. This can be a double-edged sword: companies are able to communicate with customers in more ways than ever, but brand managers need to be aware that communication is a two-way process. Customer expectations have risen accordingly and they are willing to act against companies who don’t meet their expectations. Managing communications successfully, however, can be enormously valuable to a company that recognizes the importance of its customers’ voice.

Originally published on Brian Solis Blog